Idris Isah Iliyasu

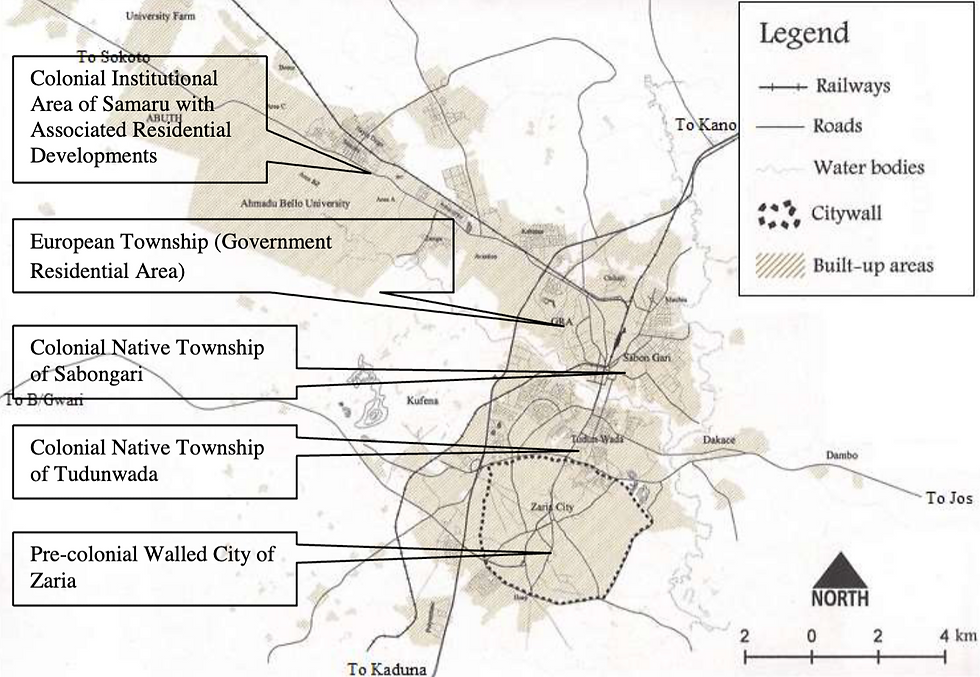

The rapid expansion of Nigerian cities in the post-colonial era has been characterised by uncoordinated growth, particularly in newly developed areas, despite initial efforts during colonial rule to implement formal planning regulations. This paper explores this phenomenon, contrasting contemporary urban expansion with the structured foundation of modern town planning established during the colonial period. Using Zaria, a historic city in Northern Nigeria, as a case study, it traces the city’s evolution from pre-colonial times to the present, highlighting the impact of weak public institutions and ineffective policies in fostering unregulated development. Zaria, originally one of the medieval Hausa cities, exhibits a tripartite urban structure shaped by pre-colonial, colonial, and post-colonial planning influences. The ancient walled city reflects traditional settlement patterns, while the colonial-era planning introduced distinct zones: the European Reservation Area, designed for British colonial officials, and native quarters for African settlers were both developed using modern, though distinct, planning approaches. However, since Nigeria’s independence in 1960, the city’s growth has been marked by uncontrolled sprawl on the peripheries of these planned areas, posing significant challenges to urban development. The study identifies weak land administration and informal land acquisition as primary drivers of this unregulated expansion, ultimately creating a paradox wherein the structured planning foundations of the colonial period have been undermined in the post-colonial era.

Zaria’s urban evolution reflects the unravelling of colonial planning and the urgent need for inclusive governance

The colonial period (1897–1960) marks a pivotal chapter in Nigeria’s urban planning history, marking the transition from indigenous spatial organisation to formalised planning introduced by British authorities. The era brought structure and institutional frameworks that reshaped Nigerian cities, including Zaria. However, this legacy has deteriorated post-independence, giving rise to widespread unregulated urban sprawl.

This pattern, evident in many Nigerian cities, reflects a broader failure to sustain and adapt colonial planning frameworks to contemporary urban governance and population dynamics. The foundation of colonial planning in Nigeria was laid by policies like the 1917 Township Ordinance, which segregated urban areas along racial and administrative lines. It led to the development of Government Reserved Areas (GRAs) for Europeans and townships like Sabon Gari for non-indigenous residents.

Though segregationist, these policies ensured some level of urban order and guided physical development. In contrast, post-independence cities are increasingly characterised by informality and haphazard expansion. This paper investigates Zaria’s physical development trajectory from pre-colonial times to the present, arguing that contemporary urban form reflects the gradual unravelling of structured planning systems initiated during colonial rule. The methodology for this study adopts a qualitative approach based on historical and spatial analysis using Maps. It utilises both secondary data from literature and primary data from field observations conducted in Zaria in December 2024.

Secondary sources include academic works, colonial planning documents, and comparative studies from other British colonies, which inform the ideological and spatial frameworks of colonial urbanism. Primary data involved reconnaissance and structured site visits to key urban areas representing Zaria’s three development epochs: the pre-colonial walled city, colonial districts (Sabon Gari, Tudun Wada, etc.), and post-colonial extensions.

A diachronic analytical lens is employed to trace how urban spatial patterns evolved under shifting political and socio-economic conditions. By triangulating literature and on-ground evidence, the research explores how colonial planning legacies have influenced Zaria’s urban morphology and the governance challenges associated with its post-independence growth.

Transformation of Zaria Urban Area

Pre-Colonial Period (11th Century – 1800s): Zaria, originally known as Zazzau, emerged as a prominent Hausa city-state in the 11th century. It later became part of the Sokoto Caliphate in 1808. Its urban structure is centred on the walled city (Birnin Zazzau), with radial roads from the Emir’s palace, markets, and Islamic institutions. Zaria played a key role in trans-Saharan trade and Islamic education.

Colonial Period (1900–1960): British colonial rule introduced major spatial changes, including the indirect rule system and the establishment of Sabon Gari for southern Nigerian migrants. The introduction of the railway in 1912 further integrated Zaria into national trade networks. Western institutions like schools, churches, and healthcare facilities were introduced. The city was divided into segregated zones, such as the GRA, native areas, and institutional districts.

Post-Independence Period (1960–1990s): Zaria’s post-independence growth was driven by the establishment of ABU and related migration. This period saw the development of new neighbourhoods and informal settlements, outpacing planning capacity. Limited industrialisation and inadequate infrastructure contributed to unregulated sprawl.

Contemporary Period (2000–Present): Recent decades have seen explosive urban growth, especially in peri-urban areas. The city retains its dual character, with the traditional walled city and Sabon Gari performing distinct socio-cultural and economic functions. However, due to weak planning and development control enforcement, infrastructure deficits and slum proliferation are the main challenges. Colonial Urban Policies and Planning Instruments. British town planning in Nigeria was structured through laws like the 1904 Cantonment Proclamation and the 1917 Township Ordinance. These codified racial and ethnic segregation, especially in cities like Zaria. Sabon Gari housed southern migrants, Tudun Wada catered to non-indigenous northerners, and Samaru developed around ABU.

Colonial Zaria was spatially divided into the following: The indigenous walled city (Birnin Zazzau), the European/Government Reserved Area (GRA), Commercial/institutional zones, and Segregated townships (Sabon Gari, Tudun Wada, and Samaru). Township layout plans from 1914, 1918, and 1939 formalised land uses, road networks, and residential plots. GRAs featured spacious plots, buffer zones, polo grounds, and access to rail and road infrastructure. These components collectively established a blueprint of structured urban form with specialised land uses and ethnic-spatial organisation.

Post-Colonial Urban Development and Contemporary Challenges. In the post-colonial era, Zaria’s urban development has become increasingly informal and unregulated. The city’s growth far exceeds the scope of its master plans. Approximately 70% of Zaria’s built-up area today consists of unplanned, often illegal developments. The contrast is stark: colonial areas like the GRA remain under-occupied but well-planned, as can be seen on the attached imagery below, while vast informal neighbourhoods accommodate most of the population.

Infrastructure in these peri-urban zones often lacks access roads, potable water, drainage, and electricity. Planning authorities are often reactive rather than proactive, and zoning regulations are routinely violated or ignored. Consequently, the legacy of colonial planning, which for all its segregationist flaws, offered structured growth which has given way to chaotic expansion and spatial inequality.

This trend highlights a planning paradox where older, colonial-era sections of the city are more systematically organized than the newer, post-independence extensions. This inverse development trajectory highlights the urgent need for revitalised planning institutions, inclusive urban governance, and investment in infrastructure and services. Zaria’s urban evolution illustrates a broader Nigerian and African dilemma: the erosion of structured colonial planning without sufficient replacement by effective post-independence urban governance.

While colonial planning was exclusionary, it introduced spatial order and functional land use. The current challenge is to reconcile this legacy with inclusive, sustainable planning models that can effectively manage rapid urban growth. Addressing urban sprawl and restoring order to cities like Zaria requires strengthening planning institutions, updating urban regulations, enforcing development control and integrating indigenous knowledge systems. The future of Zaria’s urban landscape depends on how well historical insights are leveraged to shape modern urban policy and practice.

Weak spatial governance and informal land tenure drive uncontrolled urban sprawl in zaria

Uncontrolled urban sprawl is a growing concern in many post-colonial African cities, including Zaria, Nigeria. This phenomenon is widespread across both Francophone and Anglophone African countries, although it appears to be more prevalent in Francophone regions.

The primary cause of this pattern is the dominance of informal land development, which significantly diverges from the structured urban planning principles inherited from colonial administrations, especially those influenced by British systems. Over the years, this form of unregulated urban growth has sparked numerous discussions among urban planners and the general public, indicating its longstanding recognition as a critical urban challenge.

The core of the problem lies in two interrelated issues: land tenure and land development, both of which are poorly regulated due to weak institutional frameworks. These challenges fall under the broader concept of “spatial governance,” which refers to the institutional and administrative mechanisms that guide land use, urban planning, and development. Where spatial governance is strong, cities tend to develop in a more orderly and planned manner. Conversely, weak governance results in uncoordinated, high-density urban sprawl. Post-Colonial Land Tenure in Nigeria. A key piece of legislation shaping land tenure in Nigeria is the 1978 Land Use Act, which vests all land within a state in the custody of the State Governor.

The Governor may issue statutory rights of occupancy for both urban and rural land, typically for 99 years. Local Governments, however, are limited to granting customary rights of occupancy in rural areas for only 30 years. While a formal landholder can apply for a Certificate of Occupancy (CoO) under government schemes or convert a customary title into a statutory one, the process remains bureaucratically cumbersome. As a result, most land is still accessed informally through customary tenure systems, which are less secure and often undocumented. This widespread informality means that most land is not subject to official planning controls, weakening the effectiveness of urban development strategies.

Due to the weak institutional framework for effective Urban Planning in Zaria, the responsibility for land management and urban planning is divided among several institutions, including the Kaduna State Urban Planning and Development Authority (KASUPDA), Kaduna Geographical Information System Agency (KADGIS), the local governments of Zaria City and Sabon Gari, and the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development. Among these, KASUPDA holds the central mandate for enforcing planning regulations, managing land use, and coordinating physical development within a 20-kilometre radius of the city centre. KASUPDA was created in 1985 to replace earlier colonial-era planning authorities. It operates under various legal instruments, including the 1946 Northern Nigeria Town and Country Planning Law and the federal Urban and Regional Planning Law of 1992. These laws empower KASUPDA to implement Master Plans and other development plans tailored to different urban sectors, such as housing, infrastructure, and urban renewal.

Despite its legal foundation, KASUPDA, as the apex urban planning and development enforcement agency in the state, faces significant challenges. Notably, Kaduna State has not formally adopted the 1992 federal planning law, which limits KASUPDA’s jurisdiction and effectiveness. This has created administrative ambiguities, jurisdictional overlap, and competition among institutions, particularly between KASUPDA and local governments. As a result, the authority lacks adequate financial and policy support, preventing it from controlling illegal developments or enforcing planning standards effectively.

The consequences are far-reaching: despite its technical mandate, KASUPDA often finds itself sidelined, unable to prevent rapid land speculation, unauthorised construction, and chaotic urban growth. This situation is exacerbated by the institution’s limited capacity, both in terms of legal authority and operational resources. Implications for Urban Development: The implications of these governance failures are numerous and damaging.

First, the informal nature of land acquisition makes it difficult for authorities to monitor development as it happens. Interventions often occur too late and tend to legitimise unapproved developments rather than rectify them. Attempts to enforce planning regulations, such as demolishing illegal buildings, frequently become politically and socially controversial.

Second, the lack of institutional oversight allows for rampant, unregulated land subdivision by individuals, further perpetuating the cycle of unplanned urban growth. This creates disorganised development patterns that severely complicate the provision of essential infrastructure and services, such as roads, water supply, and green spaces. Newly developed areas quickly deteriorate into slum-like conditions due to these deficits. Third, informality also leads to a lack of documentation and record-keeping.

Without accurate data on land ownership and land use, planning becomes guesswork. Authorities lack the necessary information to make strategic decisions or enforce zoning regulations effectively.

Finally, the prevalence of informal land access encourages “auto-construction» individuals undertaking construction projects without reference to any formal planning schemes or oversight. This results in low-quality developments and increases the risk of environmental and structural hazards.

Weak post-colonial governance undermines structured urban planning in Nigeria

The dynamics of informal urban expansion are commonly referred to as urban sprawl and are shaped by the interplay of economic, demographic, environmental, and spatial governance factors. The specific nature and pattern of this growth are influenced by how these forces manifest in a given context.

Central to this discussion is the role of land and planning administration in determining whether such growth is integrated into formal planning frameworks or allowed to unfold in an unregulated manner. In the colonial period, as exemplified by the case of Zaria, institutional, legal, and administrative mechanisms for land and urban planning were notably effective.

Authorities were able to designate areas for development, formalize and document land tenure, and prepare and implement layout plans for designated urban spaces. This created a structured approach to urban expansion that abandoned the planning legacy that had not been sustained in the post-colonial era, despite the availability of more human and material resources and a greater need for the principles of modern urban planning.

This paper argues that the erosion of colonial town planning legacies is a widespread phenomenon across Nigerian cities. While the underlying causes are well understood, the efforts to reverse this decline have so far fallen short of what is required. A crucial first step in addressing this issue is acknowledging its existence and raising awareness, which is the objective that this paper seeks to achieve. The insights presented here should inform both urban planning practice and theory, particularly in the Nigerian context and in other regions facing similar challenges.

Download the full article here